The Tupilaq

Note: Some historical sources cited within this article use the term ‘eskimo’ as a descriptor for the Kalaallit people of Western Greenland. ‘Eskimo’ is generally considered an outdated and generic term of reference for indigenous circumpolar peoples including the Inuit, Yupik and Aleut peoples. This article draws on the cultures of the Greenlandic Inuit, Iglulingmiut Inuit and Caribou Inuit.

Zombies have been the monster of choice within pop culture for some time now. If a movie or video game needs a metaphor for societal herd mentality, rampant consumerism, or the dangers of disease — while retaining all the joy of an action-packed gorefest in which decaying organs fly across the screen with a satisfying arc of blood and fitting squelch — then including zombies is a no-brainer.

Compared to the walking dead of yore, contemporary zombie fiction seeks out more grounded explanations for reanimating corpses — radiation, viruses, parasites, fungi — as opposed to black magic or ancient curses. But perhaps our science appealing, mass produced undead just don’t have the same bespoke allure as a concocted corpse given life by a warlock under the light of the moon. Today’s article examines the latter form of animated undead, a monstrous assassin stitched together from cadaver and carrion and set forth to claim its victim in the dark waters of the Arctic Circle — the tupilaq.

The term ‘zombie’ comes from a specific cultural heritage, that of Haitian folklore and Vodou religion. However, the concept of animating a corpse through ritual magic and commanding it to do your bidding is found in many belief systems, one of them being the religion of the Greenlandic Inuit. In this case, the ‘zombie’ creature known as a tupilaq has but one purpose: to seek and destroy its prey.

For the Greenlandic Inuit, a tupilaq was an artificial monster created by an angakkuq, a medicine man or woman, whom we might refer to as a shaman. The genesis of a tupilaq was an act of magic, a labour of song and chanted incantation practiced over several days. Materially, the beast was constructed from a slew of bone, skin and sinew scavenged from disparate animals and the corpses of children. The reanimation of this complex cadaver was no easy task. Such a foul act of magic was a serious taboo, and so the ritual had to be completed in total secrecy under the cover of darkness. The process required the angakkuq to wear their anorak backwards, placing the hood over their face. Spellcasting went beyond the mere recitation of mantras, as the shaman actually had to perform sexual acts on the pile of bones in order to charge it with virility.

Once the tupilaq was incarnated, the angakkuq was free to command it as they wished. In the folklore, this zombie was created almost exclusively as an assassin, directed like an undead missile towards a particular target. Once the intended victim was named by the shaman, the tupilaq’s hunt would begin. This creature required no sustenance, no shelter, and no rest. It would traverse mountains, swim seas, and brave blizzards, trudging forwards with the same grim intensity and single minded function. Biting the victim to death was the standard method of execution.

The angakkuq responsible for the tupilaq had to pick their target carefully. The being was a slave to magic, which meant that equally talented sorcerers could re-enchant the beast, rebounding it against its maker. If such a reversal occurred, the original shaman’s only defence was to make a public confession of their creation, nullifying the tupilaq’s offensive power.

The nature of the tupilaq varies among different Inuit cultures. In the case of the Igloolik, a tupilaq was a ghost visible only to shamans. It was a restless soul, cursed to wander due to a breach of a death taboo. This spirit could be a serious threat to the Igloolik’s livelihood by scaring game away from hunters. It was the job of the shaman to frighten the phantom away with a knife. For the Caribou Inuit, the tupilaq was a similarly invisible monster, but took the form of a chimeric beast that liked to attack settlements. This creature had to be banished by a shaman — devoured, in fact.

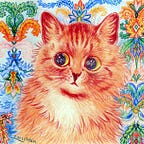

Today, the tupilaq remains a fixture of Greenlandic folklore in all its forms, but has become more associated with native art than the actual walking dead. Representations of the creature are crafted from the tusks of narwhals and walruses, the antlers of caribou, or simply from wood. The fantastic illustrations accompanying this article were produced by Kalaallit artists visualising their native folktales. Of course, 20th century anthropologists found no responsibility to credit the illustrators by name…but the book they feature in (‘Eskimo Folk-tales’ by explorer Knud Rasmussen) is available to browse online via The Public Domain Review, and features plenty more spooky spirits to enjoy.

Sources

Knud Rasmussen, ‘Eskimo Folk Tales’, translated by W. J. Alexander Worster (1913)

Wikipedia: